Industry Profile - Music

Music Industry: May 2024 Profile

Introduction

Ontario is home to the largest music industry in Canada and to an ecosystem involved in the creation, writing, production, publishing, distribution and presentation of original music. This includes musicians, songwriters, record labels, managers, music publishers, concert promoters, live music venues, presenters and more. While the sound recording and music publishing landscape in Canada includes some large, foreign-owned companies, the sector is mainly composed of strong and dynamic Canadian-owned and controlled independent music companies that are responsible for the vast majority of Canadian content that is commercially released.

Industry Size and Economic Impact

The following information on revenue, employment, and the consumer market should be considered a snapshot of activity in the industry based on the best available information.

Employment and Wages

- In 2021, the Ontario music publishing and sound recording industry generated almost 2,100 jobs, accounting for 39% of the sector’s 5,309 jobs nationally.[1] While job numbers both nationally and in Ontario, have returned to 2019 levels, they are less than in years prior.

- Ontario’s sound recording and distribution industry paid $54.7 million in employee salaries, wages and benefits in 2021.[2] This data does not include live music or music publishing. The recording studio industry paid out $21.3 million in salaries, wages, commissions and benefits in 2021, its most in the last 10 years.[3]

- The 2023 Statistical Report Profile of Music Publishers Canada and the Association des professionnels de l’édition musicale (APEM) shed light on the current state of music publishers in Canada. Compared to 2020, the publishing industry saw revenue growth of 4.3% ($12 million), mechanical rights increased from 23% to 30% in terms of revenue sources and 71% of revenues for Canadian-owned independent companies are from foreign sources. Unfortunately, when looking at employment, the survey shows no increase in jobs over the last 4 years.

- The Canadian Live Music Association (CLMA) released a new report titled Reflections on Labour Challenges in the Live Music Industry which provided a current look at the labour shortage in the live music sector in the province. The report found that coming out of the pandemic, an existing labour shortage was exacerbated by the precarious working conditions of the industry. The shortage was felt most acutely in certain roles (tech, AV), among mid-career workers. The report also found that marginalized BIPOC communities experienced labour issues more strongly.[4]

- Music Publishers Canada's recent report, Future of Work: Talent Acquisition, Retention, and DEI in the Music Publishing Industry in Canada, delved into the state of employment in the music publishing industry from a human resources lens, with the goal of developing a deeper understanding of talent acquisition, retention, diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in the sector. The report also provided a series of “right practices” that companies can adopt in their workplaces in terms of job postings, consultations with candidates, compensation review and applying an international workforce.[5]

Revenues and Related Figures

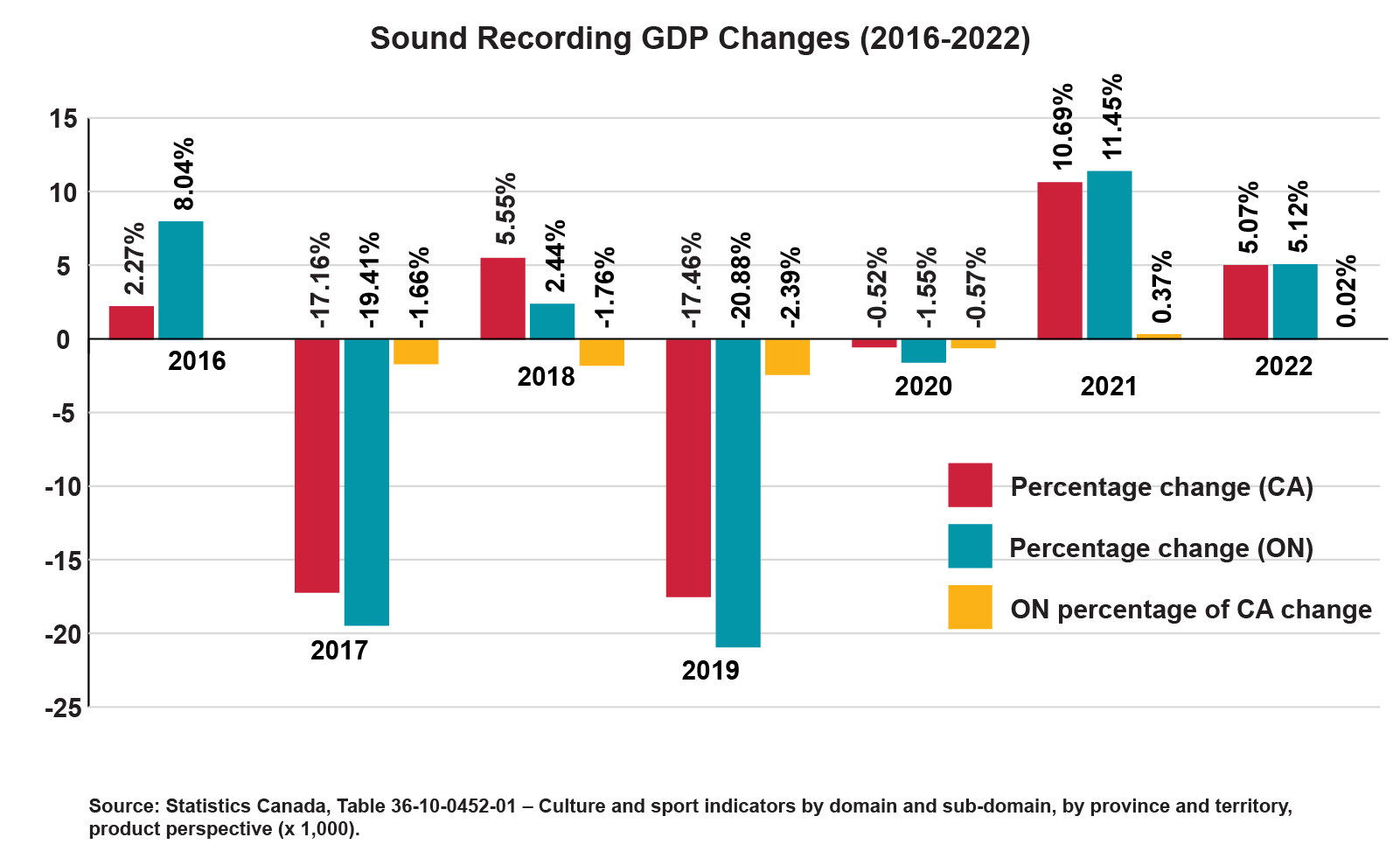

- The Ontario sound recording and music publishing industry contributed close to $215 million to Ontario’s GDP in 2021, an increase of 12% from 2020.[6] Ontario still holds a market share of 56% of the total Canadian GDP generated by the sector.

- Ontario’s sound recording and distribution industry generated over $535 million in operating revenues in 2021, with an operating profit margin of 8.7%.[7] Operating revenues saw a 23% increase from 2019, and represent 74% of industry operating revenues in the country.

- According to PwC, live music revenues reached $638 million USD in 2022, and revenues are anticipated to rise at a 4.3% CAGR to a total of $788 million USD by 2027.[8] Per last year’s PwC report (2022), live music pre-pandemic revenues were $801 million USD[9], and based on current estimates, revenues won’t return to that level until after 2027.

- In 2022, Canadian music market revenues were valued at $1.58 billion USD by PwC, with a robust digital music streaming market worth $775 million USD.[10] The growth in the digital streaming market in 2022 was estimated at 9.6%.[11]

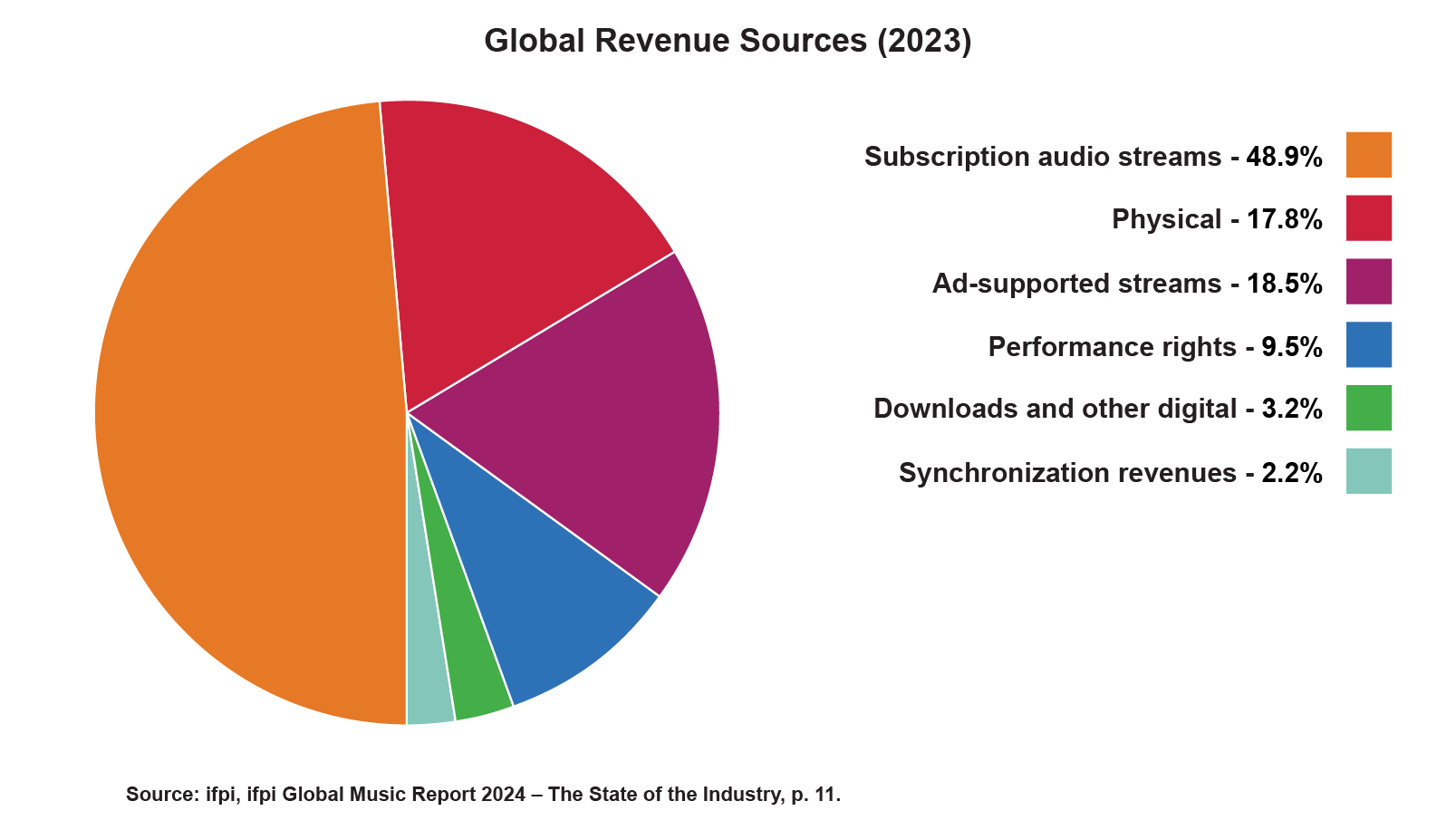

- According to IFPI, the global recorded music market grew by 10.2% in 2023, with revenue growing across all formats except digital downloads and other digital. Overall global revenues topped $28.6 billion, and marked the 9th consecutive year of growth and the highest growth rate on record.[12]

- This growth was driven significantly by overall streaming revenues, which were up 10.4%, which is the dominant music consumption format globally, and the leading revenue format in almost every single market. Streaming accounted for more than two-thirds of global market revenues.[13]

- Each of the Top 10 global markets recorded year over year growth, and China led the pack with a 25.9% increase.[14] In Canada, revenues grew by 12.2%, which outpaced the USA, who saw growth of 7.2%[15]

- For the 3rd year in a row, global physical music sales (CDs, vinyl and other physical formats) grew, and 2023 saw double digit growth of 13.4%, up from 3.8% in 2022. Revenues for physical media posted the highest growth rate of any format in 2023.[16]

- Both performance rights (9.5%) and synchronization rights (4.7%) increased in 2023, and account for 9.5% and 2.2% of the global music market respectively.[17]

- In 2022, SOCAN paid out $484 million in collections for licensed music, a 16% increase over 2021.[18] Domestic collections topped $374 million, with over a 20% increase from 2021, and Internet-related royalties, up 24%, accounted for $167 million.[19]

- Research commissioned by Music Publishers Canada and APEM highlights that their music publisher members in Canada reported $289 million in revenues in 2023, which is an annual average increase of 5.6% since 2016.[20] Moreover, 71% of those revenues came from foreign sources.[21] For Ontario-based companies, revenues from foreign sources represent 55% of gross revenues.[23]

- Ontario exported $153.4 million in sound recording products and music publishing internationally in 2021, which is still well below the over $200 million reported in 2019 and prior years [23]

Consumer Market

- Canada was the 8th largest music market in 2023, following the US, Japan, UK, Germany, China, France, and South Korea.[24]

- Canada was the 9th largest country by overall streaming volume (Total On-Demand Audio+Video) in 2023 with 145.3B streams.[25]

- Total album consumption, including physical, streaming equivalents and downloading activity, increased by 15% in 2023.[26] Total album sales continued to (physical and digital) decline and saw a decrease of 1.9%, mostly driven by a mix of digital album (-18.5%) and physical album (-11%) sales year over year.[27] Digital track sales also decreased by 16.7%, while on-demand audio and video song streaming increased by 14.6%.[28]

- Canadian on-demand audio streams passed the 100 billion mark for the first time in November 2022 on licensed platforms like Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon, and Tidal.[29]

- Looking at non-CD physical album sales (vinyl & cassettes), vinyl decreased by 2.3% in 2022, compared to 21.7% in 2021. While miniscule compared to the other formats, cassette sales increased by 26.6%.[30]

- Catalogue consumption is defined as music that has been commercially released prior over 18 months before a given point in time. In 2023, the year-over-year increase in consumption of catalogue albums in Canada increased by 17.4%, while current music album consumption also increased by 9.1%. This report found that 73.1% of music consumption was catalogue vs current releases, which made up 26.9%.[31]

- In 2022, commercial radio revenues increased for the first time in five years (2017). Revenues grew 3% overall, which was driven mostly by an 11% increase in Local Time Sales. While French language revenues declined 4%, English and Ethnic radio saw gains of 5% and 6% respectively. That being said, the compound annual growth rate has declined by 6.2%.[32]

- While traditional radio listenership continues to decline amongst the increasing adoption of online audio, data has shown that radio tuning can be seasonal with some months having more listeners than others. May has reported the highest average of tuning hours, while April has reported the least over the last 3 years.[33]

Trends and Issues

This section provides information on industry growth rates, trends, and burgeoning issues for the Canadian music industry. Key issues include music streaming services, diversity, and live performances and online shows.

Growth Rate and Industry Trends

- While COVID-19 significantly disrupted the live music industry, it has shown both resilience and newfound issues in a post-pandemic world. After two years of lows, 2022 and 2023 saw record highs for the total gross of the top 100 worldwide tours, according to Pollstar.[34] 2023 saw the top 100 tours gross close to $9.17 billion, which is an almost 65% increase from 2019. Three tours alone accounted for nearly 2 billion of the gross which were made by Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, and Bruce Springsteen.[35] Looking specifically at North American tours, Drake had the fourth highest grossing tour and was the sole Canadian in the Top 10.[36]

- Looking at the Top 100 Tours, total ticket sales increased 18.4%, average tickets per show increased by 24.25% and notably average ticket prices increased 23.33% from 2022 to 2023.[37]

- Examining venue types, all five (amphitheaters, arenas, clubs, stadiums, theatres) experienced double digit revenue growth from 2022 to 2023, with arenas and stadiums seeming 35% and 38% gains respectively. [38]

- While revenue records were being broken in 2022 and 2023, the costs of touring have increased. All facets of touring transportation, labour, insurance, production and venue costs have drastically risen in cost, causing artists and promoters to rethink touring in 2023 and beyond. One way for artists to reduce costs are acoustic tours due to less overhead, while there has also been a rise in legacy acts opting for fewer tour dates, but more corporate events.[39]

- A significant point of contention for concertgoers has been the sharp increase in concert ticket prices from the pre-pandemic era. Resale ticket prices on SeatGeek went from $116 over a three-month period in 2019 to over $240 in 2023.[40] With the secondary market on average selling tickets at double the primary seller price, which noted Live Nation President and CEO to remark “that concerts and other live events are priced below market value.”[41]

- The emergence of high end concert tickets may not subside in the immediate future. While concert production costs have increased post-COVID, Paul Biro, President of Sakamoto Agency, believes that bigger artists are still trying to make up for losses during COVID and have the ability to maximize their profits.[42]

- On April 1st, 2024, US Visa fees for touring artists (O & P Visas) will increase by over $500, from the current $460 to $1,065. This is the first time the application fees for touring musicians have been raised since 2016, and are less than the fee increase that was initially proposed. The US Citizenship and Immigration Services, which oversees the visas, claims that the increases are to “cover the cost of doing business and avoid the accumulation of future backlogs.”[43]

- IFPI’s study of the music listening behaviors in 26 of the world’s leading music markets suggests that on average, people spent 20.7 hours listening to music each week, up from 20.1 in 2022, and on average people use seven different methods to engage with music.[44]

- Short-form video platforms continue to play a key role in driving music engagement and discovery. According to IFPI, 82% of respondents aged 16-24 engaged with music via short-form video apps.[45]

- Music royalties and licensing became front page news in January 2024 when reports came out that the licensing agreement between Universal Music Group and TikTok was about to expire amid failure to renew it. Per Universal, at the heart of the dispute were three issues: appropriate compensation for artists and songwriters, protecting human artists from the harmful effects of AI, and online safety for TikTok’s users. As part of this dispute, Universal Music Group has removed their catalogue and works from Universal Music Publishing Group from the platform.[46] In May 2024, Universal announced a multi-dimensional licensing agreement with TikTok, with the release noting that the agreement will deliver “improved remuneration for UMG’s songwriters and artists, new promotional and engagement opportunities for their recordings and songs and industry-leading protections with respect to generative AI.”[47]

- High profile music catalogue acquisitions continued to make headlines into 2024 as both legacy and current artists continue to sell their repertoires. Recent Canadian catalogue acquisitions include producer Ninteen85, who sold their works to Kilometer Music Group,[48] legendary producer David Foster, who sold 100% of his writer’s share for his works to Hipgnosis Songs Capital,[49] Deryck Whibley, writer and singer for Sum 41 sold his publishing to HarbourView Equity Partners,[50] and most notably Justin Bieber sold his music rights, a deal estimated in the $200 million range.[51]

- The IFPI & Music Canada took action against nine streaming manipulation services in Canada, and all have been shut down.[52] Legitary Data, just released its latest findings in March 2024, and found that after analyzing 700 billion streams from 2022, up to 16% of streaming statements from DSP’s are suspicious, which accounts for up to $3 billion in incorrectly tracked revenues.[53] While streaming farms and streaming fraud are part of the issue, the report notes that the majority of the issue stems from data errors.[54]

- There has been a shift in recent years in terms of different territories embracing the global reach of artists. Labels are working with artists from diverse ethnicities, backgrounds and languages which can have an impact beyond ones borders. The Canadian Indian connection is very strong, and in 2022, three of the four Top 10 songs in India came from artists who either moved to Canada or spent a lot of time here.[55] Warner Music India and Warner Music Canada have entered into a joint venture[56] and were rewarded at the 2024 JUNO Awards when their artist Karan Aujla won the Fan Choice Award.[57]

- Wavelength Music Arts Projects, known for the music series and annual festivals held in Toronto, released a new research study called Reimagining Music Venues. The report looked at the current state of Ontario’s live music venues (notably as the province was emerging from COVID-19), their role as cultural centres, and opportunities to reimagine them moving forward from a preservation and innovation lens. The report put forth some recommendations to promote the longevity, innovation and growth in the provinces live music sector, which are:

- Creating a Live Music Ecosystem Observatory to gather data to help shape future policy.

- Fostering the creation/use of innovative spaces (such as mobile stage trucks) or non-traditional spaces such as parks.

- Exploring new funding models for live music.

- Advocating for new infrastructure projects (repurposing or reanimating spaces) to create new live performance locations.[58]

Global and Domestic Issues

- The current economic climate is having wide ranging impacts on the music industry both domestically and abroad. In the past year, layoffs and restructuring have taken place throughout the global music industry. Warner Music Group in February 2024 announced that they plan to cut 10% of their staff, around 600 jobs. This follows layoffs in the spring of 2023, which saw them last off 270 staff members.[59] In February 2024, Universal Music Group announced its plan to cut $271 million in jobs with an “organizational redesign”.[60]

- Record labels haven’t been the only music companies that have been downsizing as of late, but more are joining the trend. In 2022, layoffs started to ripple through the tech industry and continued through to 2023. In December 2023, Spotify announced it would be downsizing its global workforce by 17%, its third layoff of the year,[61] while fellow streamer Tidal announced a reduction of more than 10% of its staff.[62] Amazon reduced its headcount in its music streaming division in Latin America, North America and Europe in November.[63] Bandcamp cut 50% of their workforce in October after they were recently acquired by Songtradr.[64]

- The rise of artificial Intelligence and generative AI tools such as ChatGPT and Midjourney since 2022 has taken the digital world by storm. But AI technology has found it’s away into the world of music. In April 2023, a song with AI-generated voices of Drake and The Weeknd went viral on social media and streaming platforms before it was taken down due to copyright violations.[65]

- In Canada, the federal government has been conducting consultations on AI and sought input from stakeholders regarding copyright policy. Many music industry trade organizations provided feedback including Music Canada, SOCAN, Canadian Independent Music Association & Music Publishers Canada.

- Globally, the Independent Music Publishers International Forum (IMPF), made up of 200 independent music publishing companies, has issued a set of guidelines for AI developers. The guidelines focus on four core principles for the ethical use of music in AI generation.[66] They are:

- Compliance with intellectual property and copyright laws for all parties involved in AI application.

- Maintaining records of musical and literary works used in machine learning.

- Labeling of AI-generated music.

- A clear distinction of human creation and technical generation.

- The AI-generated song of Drake and The Weeknd was submitted for consideration for multiple Grammy categories, which prompted the Recording Academy, which presented The Grammy Awards, to issue a statement and clarification around AI-generated music, noting that “Only human creators are eligible to be submitted for consideration for, nominated for, or win a GRAMMY Award. A work that contains no human authorship is not eligible in any Categories.”[67]

- The JUNO Awards were quick to follow suit with their own AI eligibility guidelines. Recordings can use artificial intelligence, as long as it’s not the sole or core component of the recording. Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences president, Allan Reid noted that they are in the “learning years” in terms of AI adoption and interpretation for the awards.[68]

- Canadian musician Grimes has taken a different route with AI technology and has invited creators to use her voice for new music productions. Those looking to use her voice can register on her website and can use her voice without penalty, and plans to "split 50% royalties on any successful AI generated song that uses my voice."[69]

- YouTube announced that they will be introducing "the ability for our music partners to request the removal of AI-generated music content that mimics an artist's unique singing or rapping voice." Additionally, they will also require creators to specify if a video contains any AI-generated content before posting, in order for a warning label to be applied to it.[70]

- The 4th annual Be The Change: Gender Equity In Music report was released in March 2024, and the survey found that women and gender expansive people are for more likely to than men to experience the music industry as “generally discriminative.” 49% of women and 41% of gender expansive people held this belief.[71] While the report is worldwide, there were regional breakdowns, and it found that 65% of women in North America experienced pressure to look good, which was the highest reported figure of any region.[72]

- In May 2023, Music Canada released a research report they spearheaded in conjunction with Toronto Metropolitan University’s Diversity Institute to produce a report based on a national survey of industry professionals. The report, Enablers and Barriers to Success in Canada’s Music Industry was created with input from key professional association groups, which included the Music Canada Advisory Council, the Canadian Live Music Association, the Canadian Country Music Association, Women in Music Canada, ADVANCE and other stakeholders.[73] The study found that while actions have been taking place to reduce barriers and discrimination, there is still much work to be done. The three largest success factors mentioned were opportunities to network, collaboration opportunities and peer support. Looking at barriers, the leading barrier was financial instability, followed by inability to navigate the industry and a lack of career advancement opportunities.[74] As expected, income disparity exists in all aspects of the industry, and that the highest income earners were men, with 17% of the respondents making over $100,000 per year, while in comparison, the highest income earners among women (25%) and non-binary people (47%) earned less than $99,999.[75] Discrimination continues to persist, be it based on gender, race, or sexual orientation. Members of these groups experienced experience higher levels of job instability, lower levels of income, and more often feel discriminated against in comparison to their non-racialized counterparts.[76] A suite of recommendations are presented and are presented to tackled them at a societal, organizational and personal level, as many of the issues stem from all 3 areas of interaction within the industry. Examples include:

- showcasing and celebrating the successes of Indigenous, Black, other racialized, disability-identified, and gender-diverse talent, and highlighting diverse role models within the music industry;[77]

- creating integrated strategies for developing fair and bias-free recruitment practices;[78] and

- participating in the organizational practices and processes that contribute to diversity and inclusion in your organization.[79]

- Bell Media created a huge media shakeup in early 2024 after announcing that 45 of its 103 regional stations have been sold, amid widespread layoffs, and television programming cuts. The stations sold were in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada. This is the second layoff and radio announcement within a year, when Bell Media eliminated or sold nine radio stations in the spring of 2023.[80]

- On April 27th, 2023, Bill C-11, Online Streaming Act became law. The goal of the legislation is modernize the Broadcasting Act to include online broadcasters to address the increased prominent of online digital media. CRTC consultations began in May 2023 to help outline a new regulatory framework, review of Canadian content, and look into key policy issues. The results of the consultations and framework, including how the act pertains to music, are expected to be released in late 2024.[81]

- Bill C-27, the Digital Charter Implementation Act, is currently in consideration at the committee. The Artificial Intelligence and Data Act seeks to update Canada’s privacy laws while also introducing legislation specifically aimed at artificial intelligence. Music industry groups such as Music Canada have appeared to speak to the challenges facing the music industry around generative AI. Patrick Rogers of Music Canada also noted that the industry has made efforts to license music, but the agreements are not yet in place.[82]

- Discussions around the music industry’s role in combating climate change continue to grow and, as do the intersections between the music industry and impacts on the environment. More and more events around the topic are taking place and in Canada, Music Declares Emergency Canada will be hosting a Mini Music Climate Summit in Halifax in March 2024 prior to the JUNOS. In LA, the Music Sustainability Alliance held a summit in February 2024, with a focus on cooperation throughout the industry to help address the issues.[83]

- While the effects of climate change were felt across the country in 2023, it also had an impact on the live music sector. In Canada and across the globe, music events and festivals of all sizes were affected by heavy rain, poor air quality, extreme heat, and tornados. At least 30 major events were affected in 2023 worldwide.[84]

- In the 2024 Federal Budget, concert and sport tickets were specifically identified under Concert and Sport Ticket Fairness[85]. The budget states that federal government will work with provinces and territories to encourage them to adopt best practices for ticket sales with three priority goals:

- Ticket sales transparency (all-in pricing)

- Stronger consumer protections for Canadians (against excess fees, cancellations/refunds)

- Cracking down on fraudulent resellers and reseller practices.

Government Support

- At the federal level, support to the music industry comes through Canada Music Fund, whose individual and collective initiative streams are delivered through FACTOR in the Anglophone market, and Fondation Musicaction for the Francophone market. Announced at the 2024 JUNO Awards, Canada Music Fund will see an influx of $32 million over the next two years (2024-25 and 2025-26). This marks the first increase in funding since the 2019 budget. [86]

- Other public and private funding bodies offering support to the music industry include: Radio Starmaker (Fonds Radiostar), the Canada Council for the Arts, the SOCAN Foundation as well as the Ontario Arts Council and the Toronto Arts Council.

- The Ontario Music Investment Fund (OMIF) is a $7 million fund administered by Ontario Creates and designed to provide targeted economic development to the province’s vibrant and diverse music industry. It supports companies with strong growth potential to maximize ROI and create more opportunities for emerging artists to record and perform in Ontario. The OMIF has three streams: Creation, Music Industry Initiatives (including a sub-stream of Global Market Development for Music Managers), and Live Music.

- In 2021-22, Ontario Creates launched the AcceleratiON program, whose objective is to invest in new and emerging Black- and Indigenous-owned music businesses that demonstrate high potential for economic and cultural impact. The key goals are to enhance capacity for emerging Black and Indigenous music businesses, strengthen support at critical stages in the careers of Black and Indigenous entrepreneurs, and enable the next generation of Black and Indigenous music industry professionals to create high quality content and retain IP ownership and control over their own narratives.

- The 2023 Federal government budget proposed providing $14 million over two years for the for the Department of Canadian Heritage to support the Building Communities Through Arts and Heritage program, which supports artists, artisans, and heritage performers through festivals, events, and projects.[87]

Industry Recognition

Ontario’s music industry produces a number of critically acclaimed and best-selling artists, labels, and events.

- Ontario artists were well-represented at the 2024 JUNO Awards, which were held in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Over 40% of the JUNO winners in 2024 were based in Ontario - including multiple award winners Aysanabee, The Beaches and Tobi. Others include: Amanda Marshall, Aqyila, Daniel Caesar, Bambii, David Francey, Feist, Hilario Duran and His Latin Jazz Big Band, James Barker Band, Kirk Diamond & Finn, Kyle Brownrigg, New West, OKAN and TALK &

- The 2023 Canadian Country Music Awards were held in Hamilton, and had a strong Ontario contingent in both nominees and winners. 48% of the artist nominations went to Ontarians. OMIF supported Jade Eagleson won two awards including Entertainer of the Year and Male Artist of the Year. Other Ontario winners included James Barker Band, Dax, The Reklaws and Josh Ross who won Breakthrough Artists or Group of the Year.

- Although Ontario artists did not win any 2024 Grammy awards, they were represented with a 11 nominations. Leading the pack was Drake with 6 nominations, while the other nominees included Alvvays, Kx5, Aaron Allen, BADBADNOTGOOD and Hilario Duran.

- K’Naan was presented with a Special Merit Award for the Best Song For Social Change for his song “Refugee”. The award was presented at the Special Merit Award ceremony on February 3rd, 2024, the night before the GRAMMYs.[88]

- Six Ontario-based artists were represented on the 2023 Polaris Music Prize shortlist, including Alvvays, Aysanabee, Daniel Caesar, Feist, Debby Friday and The Sadies. The 2023 Polaris Music Prize was won by Ontario artist Debby Friday for her debut album Good Luck.

- 2023 marked the 25th anniversary of the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame, a non-profit organization that honours and celebrates Canadian songwriters. In 2023, 3 of the 4 songs inducted into the Hall of Fame were by Ontrarians, which included “Informer” by Snow, ““My Definition of a Boombastic Jazz Style” by Dream Warriors and “Echo Beach” by Martha and the Muffins.[89]

- Canadian Hip-Hop pioneer, hailed as the “Godfather of Canadian Hip-Hop” Maestro Fresh Wes was honoured with an induction into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 2024.[90]

Profile current as of April 2024

Endnotes

1 Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0452-01, Culture and sport indicators by domain and sub-domain, by province and territory, product perspective (x 1,000), released June 26, 2023.

2 Statistics Canada. Table 21-10-0055-01- Sound recording and music publishing, summary statistics, every 2 years (dollars unless otherwise noted), CANSIM (database), released March 28, 2023.

3 ibid

4 Canadian Live Music Association, Reflections on Labour Challenges in the Live Music Industry

5 Music Publishers Canada, Future of Work: Talent Acquisition, Retention, and DEI in the Music Publishing Industry in Canada, July 26, 2023

6 Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0452-01, Culture and sport indicators by domain and sub-domain, by province and territory, product perspective (x 1,000), released June 26, 2023.

7 Statistics Canada. Table 21-10-0055-01- Sound recording and music publishing, summary statistics, every 2 years (dollars unless otherwise noted), CANSIM (database), released March 28, 2023.

8 PwC, Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2023-2027: Canada, pg. 16

9 PwC, Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2022-2026: Canada, pg. 26

10 PwC, Global Entertainment & Media Outlook 2023-2027: Canada, pg. 15

11 ibid

12 IFPI, Global Music Report 2023, pg. 10

13 ibid, pg. 12

14 ibid, pg. 10

15 ibid, pg. 14

16 ibid, pg. 12

17 ibid

18 SOCAN,“SOCAN’s Member-Centric Strategy Results in 16% Surge in 2022 Revenues”, June 26, 2023

19 ibid

20 Music Publishers Canada, Profile of Members of Music Publishers Canada and of the Association des professionnels de l’édition musicale, 2023, pg. 9

21 ibid, pg. 10

22 ibid

23 Statistics Canada. Table 12-10-0116-01 International and inter-provincial trade of culture and sport products, by domain and sub-domain, provinces and territories (x 1,000,000), released October 10, 2023.

24 IFPI, Global Music Report 2024, pg. 10

25 Luminate, Year-End Music Report 2023, pg. 73

26 Luminate, Year-End Music Report, Canada 2022, pg. 6

27 ibid

28 ibid

29 ibid, pg. 2

30 ibid

31 Luminate, Year-End Music Report, Canada 2023, pg. 14

32 CRTC,Annual Highlights of the Broadcasting Sector 2021-2022, pg.6

33 ibid, pg.15

34 Pollstar Staff, “2023 Year-End Business Analysis: The Great Return Becomes Historic Golden Age”, Pollstar, December 16, 2023

35 ibid

36 ibid

37 Pollstar Staff, “2023 Year-End Business Analysis: The Great Return Becomes Historic Golden Age”, Pollstar, December 16, 2023

38 ibid

39 FYI Music News, “Higher Costs Will Impact Acts, Venues and Promoters”, Billboard Canada, September 4, 2023

40 Lora Kelly, “Why Live Music Costs So Much”, The Atlantic, June 29, 2023

41 Daniel Tencer, “The Concert Ticket Market Is ‘Dramatically Underpriced’… And 3 Other Things We Learned From Michael Rapino On Live Nation’s Q1 Earnings Call”, Music Business Worldwide, May 9, 2023

42 Natalie Harmsen, “Music fans won't get a break on concert ticket prices in 2024, according to experts”, CBC, Jan 29, 2024

43 Megan Lapierre, “US Visa Fees for Touring Artists to Increase by More Than $500 in April”, Exclaim, February 13, 2024

44 IFPI, Engaging with Music 2023, pg. 4

45 ibid, pg. 8

46 Jem Aswad, “TikTok Begins Removing Universal Music Publishing Songs, Expanding Royalty Battle”, Variety, February 27, 2024

47 Universal Music Group, “Universal Music Group and TikTok Announce New Licensing Agreement”, May 1, 2024

48 Kilometer Music Group, “Kilometre Music Group Partners with Grammy-winning Producer Nineteen85”, November 8, 2022

49 Kristen Robinson, “David Foster Sells Writer’s Share of Performance Royalties to Hipgnosis”, Billboard, April 19, 2023

50 Ed Christman, “Sum 41’s Deryck Whibley Sells Publishing Catalog to HarbourView”, Billboard, August 18, 2022

51 Jem Aswad, “Justin Bieber Sells Music Rights to Hipgnosis Songs for $200 Million-Plus”, Variety, January 24, 2023

52 Dylan Smith, “IFPI Touts Fake Stream Takedowns in Canada, Says Manipulation Services ‘Cannot Be Allowed to Continue to Divert Revenue Away from the Artists’”, Digital Music News, March 14, 2024

53 Paul Reskinoff, “Legitary Data Shows That 16% of All Music Streams Are ‘Suspicious’ — But Streaming Fraud Is Only Part of the Problem”, Digital Music News, March 14, 2024

54 ibid

55 IIFPI, Global Music Report 2024, pg. 32

56 ibid

57 Anurag Tagat, “Karan Aujla Wins Juno Fan Choice Award”, Rolling Stone India, March 25, 2024

58 Wavelength, Reimagining Music Venues

59 Jem Aswad, “Warner Music to Lay Off 10% of Staff in Effort to ‘Double Down on Core Business’”, Variety, February 7, 2025

60 Ashley King, “Major Layoffs Ahead at Universal Music Group as ‘Strategic Organizational Redesign’ Looms”, Digital Music News, February 28, 2024

61 Marc Schneider, “Spotify Slashes Global Workforce By 17% in Latest Cost-Cutting Effort”, Billboard Canada, December 4, 2023

62 Aisha Malik, “Tidal is cutting 10% of its staff as parent company Block seeks to reduce headcount”, Tech Crunch, December 7, 2023

63 Greg Bensinger, “Amazon cuts jobs in music streaming unit”, Reuters, November 8, 2023

64 Devin Coldewey, “Bandcamp’s new owner lays off half the company”, Tech Crunch, October 16, 2023

65 Chloe Veltman, “When you realize your favorite new song was written and performed by ... AI”, NPR, April 21, 2023

66 Mandy Dalugdug, “GLOBAL INDEPENDENT MUSIC PUBLISHERS PROPOSE SET OF ‘ETHICAL’ GUIDELINES FOR AI DEVELOPERS”, Music Business Worldwide, October 9, 2023

67 Jem Aswad, “Grammy Chief Harvey Mason Clarifies New AI Rule: ‘We’re Not Giving an Award to a Computer’”, Variety, July 5, 2023

68 Megan Lapierre, “AI-Generated Drake, the Weeknd Song Not Eligible for JUNO Either”, Exclaim, September 13, 2023

69 Vanessa Romo, “Grimes invites fans to make songs with an AI-generated version of her voice”, NPR, April 24, 2023

70 Ben Okazawa, “YouTube Will Allow Music Publishers to Regulate AI-Generated Music”, Exclaim, November 13, 2023

71 Katie Bain, Half of Women in Music Industry Say Gender Discrimination Persists, New Report Finds, Billboard, March 8, 2024

72 ibid

73 Regan Reid, “Enablers and Barriers to Success in Canada’s Music Industry”, Music Canada, May 24, 2023

74 Music Canada, Enablers and Barriers to Success in Canada’s Music Industry, pg. iv

75 ibid

76 Ibid, pg. vi

77 Ibid, pg. 64

78 ibid

79 Ibid, pg. 65

80 Sammy Hudes, “Bell ends some CTV newscasts, sells radio stations in media shakeup amid layoffs”, Toronto Star, February 8, 2024

81 CRTC, Modernizing Canada’s broadcasting framework

82 Anja Karadeglija, “Canadian TV, film, music industries ask MPs for protection against AI”, CityNews, February 12, 2024

83 Kate Bain, “At the Music Industry’s First North American Climate Summit, Cooperation — Not Competition — Is the Focus”, Billboard, February 9, 20234

84 Katie Bain, “Here Are All The Concerts Affected By Climate Change In 2023”, Billboard, October 20, 2023

85 Canadian Budget, Budget 2024

86 Canadian Heritage, “Canada’s music creators to benefit from $32 million in funding for the Canada Music Fund” Canada, March 24, 2024

87 Canadian Budget, Budget 2023

88 Rosie Long Decter, K'naan Wins Recording Academy Social Change Award For "Refugee", Billboard Canada, January 8, 2024

89 SOCAN Magazine, CANADIAN SONGWRITERS HALL OF FAME INDUCTS FOUR ‘80S, ‘90S HIT SONGS AT “LEGENDS” EVENT, November 7, 2023

90 The Canadian Music Hall of Fame, “Maestro Fresh Wes”